Dynamite

Nothing seems quite so paradoxical as the inventor of dynamite being the sponsor of the World’s most renowned peace award – The Nobel Prize.

Nothing seems quite so paradoxical as the inventor of dynamite being the sponsor of the World’s most renowned peace award – The Nobel Prize.

That being the case the invention of Dynamite, please note NOT gunpowder, was a pretty seminal moment in the history of technology. As we shall see it’s use in engineering projects has helped to power and transform our modern world.

An Idea Whose Time had Come

Up until the middle of the 18th century, gunpowder was the only important explosive known to man. By that time it had been known in Europe for several hundred years so that a more powerful and controllable explosive force seemed to be one of those inventions that people seemed to be waiting for.

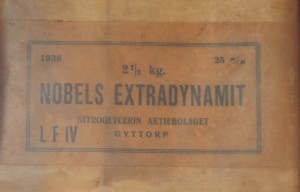

Dynamite or ‘Nobel’s Safety Blasting Powder’ when it arrived meant that Alfred Nobel, its’ inventor, had to waste no time persuading people to try his product.

Dynamite or ‘Nobel’s Safety Blasting Powder’ when it arrived meant that Alfred Nobel, its’ inventor, had to waste no time persuading people to try his product.

Men were greedy to use this new violent power, to get hold of this explosive which could blow up mountains and tunnel out mines. In fact, Nobel had to spend his time trying to stop people from making and selling dynamite without paying him royalties on his patents. In the end he managed to keep most of the manufacture of his inventions under his own control, and as a result he became an extremely rich, international tycoon, with factories all over the world.

Explosives very quickly became vital commodities both to industry and to war.

Nowadays, high explosives mean military weapons to most of us. However Alfred Nobel always said that he did not want the explosives he invented to be used for war, ‘the horror of horrors and the greatest of all crimes’. They were needed for peaceful jobs in mining, industry and transport, to build roads and railways, quarry metals and blast mountains. The great engineering projects of the two hundred years would have been impossible without dynamite. But governments quickly saw the war potential of a really powerful explosive, and military engineers designed devastating new weapons using dynamite. And Nobel himself became very interested in the technical side of fire-arms, inventing and patenting many improvements.

A Complex Man

Alfred Nobel lived a life full of contrasts. He was shy, lonely and hated publicity, yet dynamite is one of the most familiar patented names in the world. He always thought of himself as a Swede, although he only lived in Sweden until he was 9 years old, returning for brief periods. He was a sickly child, with very little schooling, and a frail man. Yet he worked himself unbelievably hard, and was a great inventor and industrialist as well as being widely read and fluent in 5 languages. He wanted to be an inventor all the time, and his happiest days were spent in his laboratory, experimenting. Yet he quickly became a powerful international financier continually involved in law suits and business problems. He was an idealist, yet he has been condemned as the inventor of great destructive forces.

Alfred Nobel lived a life full of contrasts. He was shy, lonely and hated publicity, yet dynamite is one of the most familiar patented names in the world. He always thought of himself as a Swede, although he only lived in Sweden until he was 9 years old, returning for brief periods. He was a sickly child, with very little schooling, and a frail man. Yet he worked himself unbelievably hard, and was a great inventor and industrialist as well as being widely read and fluent in 5 languages. He wanted to be an inventor all the time, and his happiest days were spent in his laboratory, experimenting. Yet he quickly became a powerful international financier continually involved in law suits and business problems. He was an idealist, yet he has been condemned as the inventor of great destructive forces.

Nobel had an extraordinary father, Immanuel, who was always working on inventions and schemes to make money. These often failed, which left the family very poor. When Alfred was 9 his father summoned the family to Russia, to St Petersburg, where he had set up a factory making military weapons, machine tools, and central-heating pipes. Immanuel Nobel’s factory was very important in starting the Russia of the Czars on its industrial revolution. But after some years a new Czar closed the factory, though Alfred’s two elder brothers stayed on and eventually founded Russia’s huge oil industry. Alfred did his first experimenting with explosives in St Petersburg.

Prelude to Dynamite – Nitroglycerine

In 1846, when Alfred Nobel was only 13, an Italian chemist called Ascanio Sobrero made an explosive so dangerous he begged everyone to forget about it. Sobrero added glycerine to nitric and sulphuric acids, then poured the compound into a basin of water. The pale-yellow oil which sank to the bottom was called nitroglycerine. It was not detonated by a spark or flame, like gun-powder, but by impact – percussion. Drop a small bottle of nitroglycerine in the laboratory, and the whole building would be blown sky-high.

Alfred became fascinated by this sensitive, risky, but extra-ordinarily powerful, new oil. For centuries the only available explosive had been gunpowder, which was useful but limited. Alfred and his father were now back in Sweden, and both began experimenting with nitroglycerine, separately. Alfred Nobel was determined to find a way to control the detonation of nitroglycerine – the size and the timing of the explosion.

In 1863 he invented the blasting cap, which effectively detonated nitroglycerine by means of a small explosion of gunpowder. It was a new and vital technique in the science of explosives. Alfred was now certain that nitroglycerine had an enormous future. But the public was most suspicious about the explosive. After a lot of trouble, Nobel was given permission to start manufacturing nitroglycerine with the blasting cap – he called it ‘Nobel’s Blasting Oil’ – on board a barge moored in the middle of a Swedish lake. Then, in 1864, a terrible explosion destroyed the Nobels’ experimental workshop in the garden of their home, killing, among others, Alfred’s younger brother, and shattering his father’s health. The situation was critical. Reports kept coming in of appalling accidents. People so often just did not realize how the slightest shock, or even change in temperature, could cause the risky oil to explode. There were dreadful difficulties in transporting it, particularly overland, or round the coast to California where goldminers wanted to get their hands on the explosive at any cost.

Dynamite

A way had to be found of making nitroglycerine less dangerous, safer to transport, yet as powerful.

In 1864 Nobel decided to try using kieselguhr, a very porous kind of earth found in certain places: for example, in northern Germany. He discovered that it soaked up the nitroglycerine without changing its chemical composition; the resulting mixture could be made into hard cakes or sticks. Here was the answer. Nobel patented his invention in 1867, and called the new explosive ‘dynamite’ (after the Greek word dunamis meaning power). Dynamite was really nitroglycerine, tamed.

Now Nobel hurried to patent this invention in major European countries, to get it made in his factories, and organize ways of transporting it wherever it was needed. It was a restless, nerve-racking life. Some governments, frightened by nitroglycerine’s power, and prodded by public horror at explosion accidents, refused to allow it to be imported into their countries. The big gunpowder manufacturers tried to stop it. The French government would not let Nobel build a dynamite factory in France, until war with Germany in 1870 forced them to insist on it in a hurry.

German sappers used the new explosive to blow up age-old French forts and bridges. In Great Britain, after restrictions and delays, Nobel built his dynamite factory on the lonely west coast of Scotland, at Ardeer. For twenty years all railways in England refused to carry nitroglycerine explosives. So Nobel had to arrange for transport by horse and cart. Later the company organized its own fleet of specially-built steamers.

German sappers used the new explosive to blow up age-old French forts and bridges. In Great Britain, after restrictions and delays, Nobel built his dynamite factory on the lonely west coast of Scotland, at Ardeer. For twenty years all railways in England refused to carry nitroglycerine explosives. So Nobel had to arrange for transport by horse and cart. Later the company organized its own fleet of specially-built steamers.

In the United States, Nobel found competition from unscrupulous businessmen determined to get in on the profitable explosives trade so distasteful that he swore never to return. Vigorite, Rendrock, Hercules, Railroad-Powder appeared on the market in America – explosives made to Nobel’s formula with tiny changes.

Despite all the official restrictions, everyone wanted to use Nobel’s explosives. Within 6 years of patenting dynamite, Nobel had sixteen factories in twelve different countries. At the’ time of his death, a little over 20 years later, 93 factories all over the world produced 66,500 tons of dynamite a year. Ninety years after dynamite was patented, over 400,000 tons were produced annually in the United States alone. So the business grew, gathering allied concerns into huge new industrial group.

His Legacy

Nobel was interested in all kinds of things besides explosives: synthetic rubber, blood transfusions, improvements to the telephone, aerial photography.

Nobel died in 1896. He left a four-page will, made the year before at his Paris home, written in Swedish. It was a remarkable will:

The capital … shall constitute a fund, the interest of which shall be annually distributed in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.

The said interest shall be divided into five equal parts, which shall be apportioned as follows: one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics; one part to the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who shall have made the most important: discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work of an idealist tendency; and one part to the person who shall have done the most or the best work to promote fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses. … It is my express wish that in awarding the prizes no consideration whatever shall be given to the nationality of the candidates, but the most worthy shall receive the prize, whether he he a Scandinavian or not.

There was a terrible fight over Nobel’s will. What did it mean? How could it be carried out? The newspapers were very critical – the will should be declared invalid. How unpatriotic of Nobel to ignore Swedish interests in favour of international activity. It would cause nothing but trouble and quarreling. But several devoted friends worked hard untangling all the legal, financial and political problems, trying to interpret Nobel’s wishes. The Nobel Foundation was set up in 1900, and the first awards were made the next year.

Nobel Prizes today are perhaps the most valued prizes in the world. They are distributed in a solemn ceremony every year on 10 December, the anniversary of Nobel’s death. Alfred Nobel’s name stands for much more than dynamite.