The RGLI – Royal Guernsey Light Infantry

The First World War has become a byword for slaughter on an unimaginable scale. It changed the world forever marking a watershed between an ‘old style’ of war that revolved around cavalry, marching infantry and gentlemen officers and a new one of ‘total war’, war on an industrial scale where the railway and factory created a new mechanised form of killing. At the time it was described as “the war to end all wars” however in retrospect it would be better to view as it as “the war to change all wars”

No country in Europe was immune from its effects and Guernsey was no exception. In this article we look at the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry or R.G.L.I which was Guernsey’s patriotic response to Britain’s call to arms and the terrible consequences it reaped on local life. We also have an article where you can view a timeline of the RGLI along with many more photographs.

We also have articles on the Guernsey men who fought alongside both the the Irish and Scottish in WWI : ‘ The Guernsey Irishmen ‘ and ‘ The Guernsey Scottish ‘.

THE OUTBREAK OF THE WAR

Sarajevo

Europe was a particularly unstable place in 1914. Germany was increasingly feared not only because of her military strength but also because she was building up a new and powerful navy.

In addition, Germany’s new political drive encouraged growth and acquisition of territory around the globe. This contributed to a highly flammable situation amongst the European states which a single incident could ignite into violence. That incident occurred in Sarajevo.

The Flashpoint

On 28th June 1914, the heir to the Austrian Empire, Franz Ferdinand, was visiting Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. Franz and his wife were shot dead by Gavrilo Princip who was a member of the Serbian secret society known as “The Black Hand”.

Austria’s response to this heinous act was to declare her intention to invade Serbia. The Serbians called for help from their old allies the Russians who mobilised their army. Austria’s allies, the Germans, then declared war on Russia. France responded by stepping in to support her allies, the Russians.

On 4th August 1914, Germany invaded Belgium with the intention of pushing through into France. Honouring a pledge she had made back in 1839. Britain came to the defence of Belgium and declared war on Germany.

For a more detailed look at the causes of the war see our article The Domino Effect – How Europe fell into World War I

The First World War had Begun.

Britain sent 120,000 Regular Army soldiers in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France However, Germany’s army was much larger By the end of 1914 the BEF had helped to bring the German advance across Europe to a halt, but the British force had been practically wiped out. The huge losses were at first made up by soldiers from British Territorial Army units but more men were desperately needed. Fortunately Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, had realised the scale of the coming conflict and began to raise a volunteer force. These volunteer Divisions were to bear the brunt of the horrors to come.

GUERNSEY RESPONDS

Off To The Front

As Europe went to war in 1914, the Royal Guernsey Militia was mobilised to replace the regular army garrison which was withdrawn to join the British Expeditionary Force m France and Flanders.

Militiamen could not be sent overseas but the States decided to offer a contingent of trained men to the British Government. Two full strength infantry companies and a machine gun company were sent to join the 16th (Irish) Division which was forming in Ireland as part of Kitchener’s all-volunteer army. One company was attached to 6 Royal Irish Regiment and the other to 7 Royal Irish Fusiliers. The machine gun company went to 6 Royal Irish Fusiliers.

A Divisional Ammunition Column was formed from the Royal Guernsey Artillery and sent to 9th (Scottish) Division. The 16th Division took part in the fighting on the Somme in 1916 and at Messines and Ypres in 1917. The Guernsey Companies suffered heavy casualties.

By 1917 a large proportion of the Islands’ fittest men were at the Front, leaving the Bailiwick with a depleted workforce. Farmers and growers often appealed to the Tribunals for men to be spared from active service for essential jobs on the land. Few were granted more than a few months’ respite. Many young women had also left the island to do war work such as nursing or working in munitions factories. Some made uniforms or worked in canteens for the troops. Others joined the newly formed Women’s Legion, which became the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Those who remained took on jobs which were traditionally done by men such as greenhouse hands, tram conductors and drivers. Women also worked in shops, banks and offices. Many also did voluntary work, such as helping in the communal kitchens which were set up to feed schoolchildren when food and fuel shortages began to hit the island.

BIRTH OF THE RGLI

Creation and Training

Meanwhile, throughout England and her colonies men rushed to join the fight. By the end of 2.6 million men had volunteered for service in Lord Kitchener’s ‘New’ Army.

Conscription was introduced in January 1916.

Under pressure from the Lieutenant Governor Sir Reginald Hart, the States of Guernsey agreed that they would raise a full infantry battalion for the British army. In the spirit of the time it was felt that Guernsey should be seen to be ‘doing its bit’ by fielding a unit with its own name.

As a result, at the end of 1916 the Militia was suspended for the duration of the war and the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry was raised as part of the British army. Most of the initial officers and men were former members of the Militia, but later drafts were not.

The Guernsey men underwent basic training on L’Ancresse and at Les Beaucamps and Fort George. The training included digging trenches, route marches, fitness training and drill instruction. The men were also given weapons training which included musketry and bayonet practice.

Once this was accomplished, a big parade was held on L’Ancresse Common. Medals were presented to soldiers who had served with the volunteer companies but who were now with the R.G.L.I. after convalescing from wounds received in action. The battalion also received a set of regimental Flags sewn by the ladies of Guernsey.

The RGLI Sail Away to War

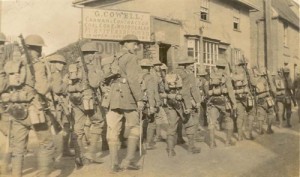

After completing its basic training in Guernsey the battalion was ready to transfer to England. On 1st June 1917 the majority of the 1st Battalion R.G.L.I, marched down to the White Rock in St. Peter Port harbour where throngs of cheering Islanders waved them aboard a steamship.

The Guernseymen travelled to Bourne Park Camp near Canterbury where they stayed for just under 4 months receiving advanced infantry training. After a final period of leave, 44 officers and 964 other ranks sailed for France on 26th September.

On their arrival they were attached to 29th Infantry Division, which was commanded by a Guernseyman, Major-General Beauvoir de Lisle. The men of the R.G.L.I. were posted to 86th Brigade and were transported by cattle-train to Stoke Camp in Proven, Flanders (now part of Belgium, France and the Netherlands).

The Division was made up of regular army battalions and had recently served with considerable distinction in Gallipoli. However by the time the R.G.L.I. joined many of the old regular soldiers had become casualties. It is likely that the arrival of the fresh Guernsey troops provided a much needed boost to morale and motivation for the battalions around them.

THE RGLI IN FRANCE

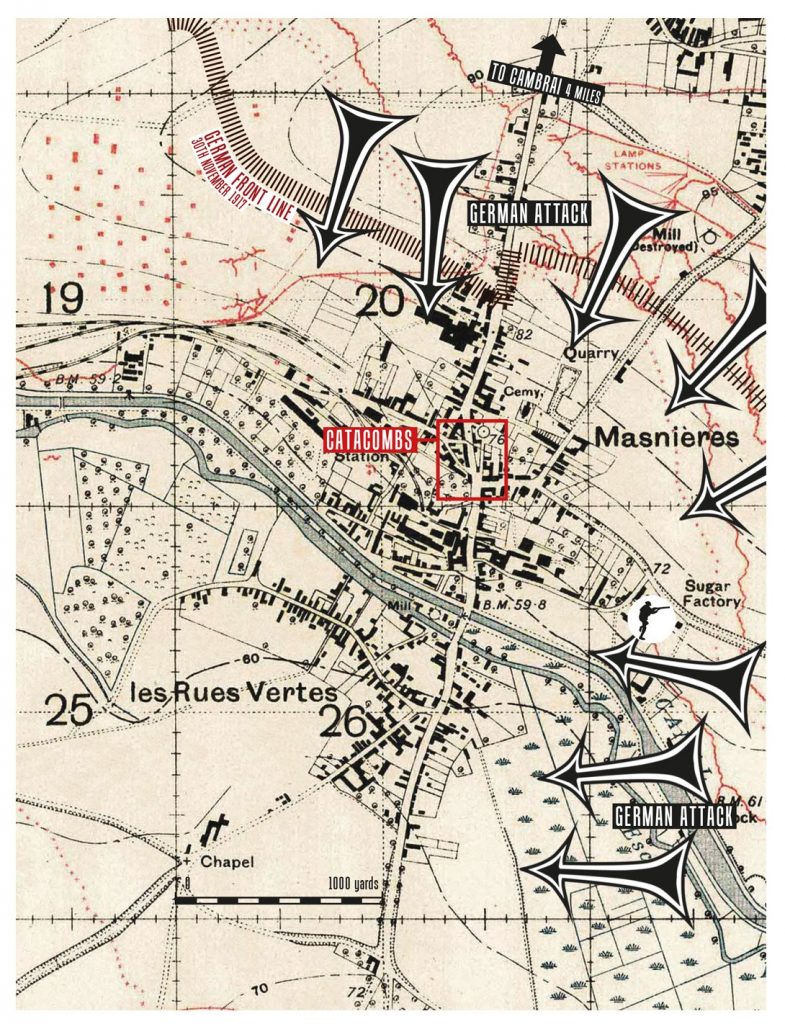

The Battle of Cambrai : 20th November-5th December

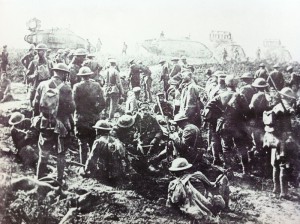

By November 1917 the war had been raging for three years. On the ‘Western Front’, the French and the British were locked in a brutal stalemate with the Germans and the casualties on both side had run into millions.

The original idea behind the Battle of Cambrai was a kind of large scale tank raid on the German rear areas with the aim of destroying enemy personnel, guns and supplies as well as sapping their morale. The tank was still in its infancy and nobody was quite sure how best to use it or what effect it would have on the enemy.

In the end the plan was expanded into a major operation with the objective of pushing the Germans back a considerable distance.

The initial attack succeeded beyond the planners’ wildest dreams and almost all the objectives were achieved with minimal casualties. The R.G.L.I. took their objective called Neuf Bois (or Nine Wood) which was far behind the German front line. Only one officer and two soldiers were killed and 25 men were wounded.

But retribution was not far away. Ten days later the Germans launched a massive counter-attack. The Guernseymen were ordered to hold a little village called Les Rues Vertes on the outskirts of Masnieres along the River Escaut. Twice they were pushed out of the ruins by sheer weight of numbers and twice they retook the Village at the point of a bayonet.

But retribution was not far away. Ten days later the Germans launched a massive counter-attack. The Guernseymen were ordered to hold a little village called Les Rues Vertes on the outskirts of Masnieres along the River Escaut. Twice they were pushed out of the ruins by sheer weight of numbers and twice they retook the Village at the point of a bayonet.

Sadly however such valour does not come cheap and by the end of the fighting 40% of the battalion’s total strength of 1,311 men were dead, wounded or missing. It seemed like the end of a generation in Guernsey and the island watched in disbelief, as the casualty returns grew and grew until there was hardly a family in the Island that had not lost a loved one.

The Survivors

Because of the huge losses suffered by the battalion there was no question that the R.G.L.I, would be able to go back into the line in the foreseeable future.

The casualties from Cambrai were so great that the RGLI was threatened with disbandment. However the Govenor, Sir Reginald Heart, began pleading for the unit to stay intact.

Guarding the Commander in Chief

Whilst the Govenor endeavoured to save the RGLI from disbandment the battered and bloody remnants of the 1st Battalion were ordered to report to Ecuires where they took over as guard troops on Field Marshal Douglas Haig’s headquarters at Montreuil.

It was whilst here that they started to receive a number of new drafts of men that Governor Heart had managed to procure. Particularly, these were ; 200 men from 3rd Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment; 28 men from training battalions and more from Durham light infantry, most of whom were recovering from wounds. He also managed to get men from the Worcestershire Regiment + even from the Jersey Militia!

The Regiment as a fighting unit was saved.

Back in the Line : January 1918

In January 1918, reinforced and ‘rested’, the Battalion went back into the line at Ypres in Passchendaele, relieving the 2nd Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment and the 1st Royal Irish Rifles (amongst whom there were some Guernseymen – still serving with the Irish).

During this 1st period the RGLI repelled a major attack with 7 killed & 25 wounded.

The RGLI then remains in the Passchendaele area taking turns in and out of line until April 1918.

In March, the proportion of ‘Guernseys’ in the battalion received a boost when 65 Guernseymen, from the Royal Irish Regiment & the 7th Royal Irish Fusiliers, re-join their fellow islanders when these two battalions are disbanded.

Operation Michael and Georgette

On the 21st March 1918, with the Russians out of the war and the Americans arriving in ever increasing numbers on the Western Front the Germans launched their last desperate bid to break through and win the war with ‘Operation Michael‘.

The German strategy for the 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle), involved four offensives, Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau and Blücher–Yorck. Michael took place on the Somme whilst Georgette was conducted on the Lys and at Ypres. It was into Georgette, in April, that the RGLI was sucked into the maelstrom.

In early April the 29th Division, of which RGLI was a part, was pulled out of the line and hurried south by lorry to Lys – an area South of Bailleul. The Germans had broken through the line & were advancing on the vital railhead at Hazebrouck. The 29th, 86th & 88th Brigades were deployed to meet them.

So, on the 10th April 1918, the Regiment found itself in Doulieu, The next day at 2:00 pm they engaged the advancing Germans. B & C Companies were virtually wiped out whilst A & D companies along with Battalion HQ fought on to hold the line until they are forced to withdraw to a position just east of Doulieu. Doulieu was subsequently by-passed by the Germans.

By the end of 12th April, after more heavy fighting and heavy casualties, the Guernsey’s were outflanked so that the Battalion had effectively been by pushed aside by the advancing Germans.

However, it wasn’t until the April 14th that the RGLI was relieved from the line by Australian troops. After 3 days of heavy fighting, and of the 20 officers & 483 men who had originally marched into Doulieu, Colonel de Havilland brought out just 3 officers & 55 other ranks. A further 47 had become detached & had joined up with other units. Many of the wounded had been abandoned during the retreat with many small groups of officers & men cut off & forced to surrender.

Despite this though the British Army had stopped the German advance and what would happen next would ultimatley see the allies victorious.

Guarding the C-in-C Again

On 27th April 1918, the much depleted RGLI were posted to Ecuires to act as guard troops at Haigs HQ in Montreuil. Again whilst here they retrain & receive recruits from the 2nd (Reserve) Battalion in Guernsey. Their war though is effectively over.

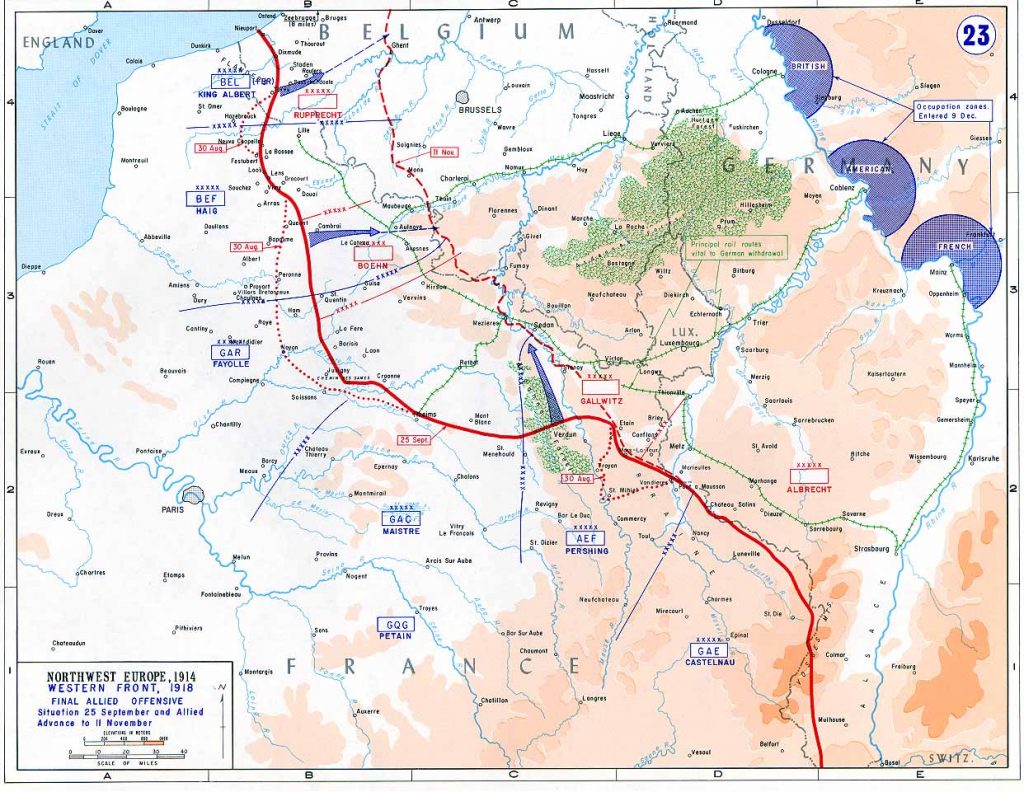

The Allies ‘100 Days Offensive’

On the 8th August 1918, after the allied retreats in March, the allies start their 100 Days Offensive – the final period of the War. During this time the Allies launched a series of offensives on the Western Front from 8 August through to 11 November 1918. It began with the Battle of Amiens and finally broke the deadlock of trench warefare. From this point on the fighting will range across open French countryside and will push the Germans out of France.

On the 8th August 1918, after the allied retreats in March, the allies start their 100 Days Offensive – the final period of the War. During this time the Allies launched a series of offensives on the Western Front from 8 August through to 11 November 1918. It began with the Battle of Amiens and finally broke the deadlock of trench warefare. From this point on the fighting will range across open French countryside and will push the Germans out of France.

Finally on 11th November thwe Armistice was signed, just in time for the Guernseys, as the RGLI was under orders to go back into the line at that time.

THE RETURN TO GUERNSEY

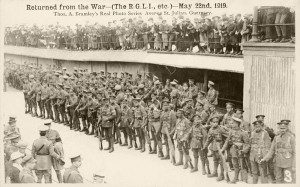

May 1919

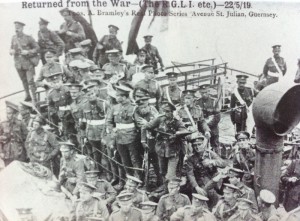

In May 1919 the battalion returned to Guernsey. Hardly any family in Guernsey was left untouched. We can only guess at the relief,joy and sadness felt by the surviving Guernseymen on their return home whilst remembering all the good men left back in France.

Returned from the War. parading on the White Rock after Disembarking (with kind permission from deanephotos.com)

The Cost

Many Guernseymen had suffered years of captivity in Germany whilst many more carried home grievous wounds of both body and mind. The R.G.L.I. left behind them 327 graves in France. The war had been won, but at a terrible cost which was felt in every home in the Island.

The total number of men who served in the R.G.L.I. was 3,549 of whom 2,430 were recruited in Guernsey. The remainder were transferred from England.

Of the 3,549 men of the R.G.L.I., 2,280 served in France with the 1st (Service) Battalion.

THE FOLLOWING HONOURS WERE AWARDED TO THE R.G.L.I.:

| OFFICERS | |

| 1 Companion of the Order of St. Michael & St. George | |

| 5 Military Crosses (3 with Citations) | |

| 1 Member of the Royal Victorian Order | |

| 1 Croix de Guerre | |

| 5 Mentioned in Despatches | |

| MEN | |

| 3 Distinguished Conduct Medals | |

| 6 Military Medals | |

| 1 Medaille Militaire | |

| 1 Croix de Guerre | |

| 5 Mentioned in Despatches | |

| THE FOLLOWING CASUALTIES WERE SUSTAINED | |

| 667 | WOUNDED |

| 225 | PRISONERS OF WAR |

| 30 | DIED OF SICKNESS |

| 67 | DIED OF WOUNDS |

| 230 | KILLED IN ACTION OR MISSING, PRESUMED DEAD |

| 327 | TOTAL LIVES LOST |

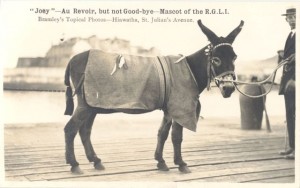

The Royal Guernsey Light Infantry chose a Guernsey donkey called Joey as their mascot. Joey left the Island on 1st June 1917 and travelled with the 1st(Service) Battalion of the R.G.L.I. to Bourne Park Camp near Canterbury. Joey remained at the Camp whilst the battalion underwent their Advanced Infantry Training. The donkey returned to Guernsey when the battalion departed for France to enter the War.

Joey was given a ‘coat’ which bore the Regiment’s ‘battle colours’.

Battle colours were worn in the form of a ‘patch” or fabric badge on a soldier’s uniform when he was in combat The patch enabled the soldier’s Regiment to be easily identified. In 1917 the R.G.L.I.’s battle colours were green and white. When the men of the 1st (Service) Battalion left the Island in June that year the ribbons that decorated the donkey’s coat were this colour. When the battalion entered the Battle of Cambrai in November they wore a green and white patch on the back of their collars.

Sometime during 1918 this patch was replaced with a new one coloured buff and blue, which was worn by the men on each shoulder and also below the collar on the back of their uniforms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.