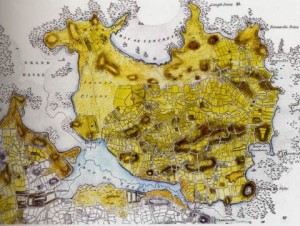

When there were two Guernseys

Sand, gravel, clay and bogs – the Braye du Valle literally split the island in two and reclaiming the land was a massive engineering feat. The year was 1803 and it was the fear of the French landing on the undefended and isolated Clos du Valle that gave Guernsey’s Lt-Governor most cause for concern.

Origins

Since gaining independence from mainlaind France in 1204 the Channel Islands were faced with the continual threat of invasion by the French. By the 18th and early 19th centuries the threat was so great that English Regiments were permanently garrisoned in Guernsey and every able bodied Guernseyman was required to serve in the local Militia. Never was the threat so great as during the French Revolutionary wars and the subsequent Napoleonic wars with Britain. In 1800 the Guernsey Militia alone numbered 3,158 men of all ranks plus 450 boys. This is a stagering size given the island population at that time and indicates the level of threat posed to the islands. It’s against this backdrop that the then Lt-Govenor, Sir John Doyle, initiated a programme of major projects to improve the island defences, one of which was to re-unite the 2 islands.

The Braye du Valle was a mixture of sand, gravel, clay and bogs that was flooded at high tide. It was initially created by rising sea levels in the Middle Ages when the sea burst inland over the low-lying land in the north of the island cutting the Guernsey in two and creating the Braye du Valle.

The marshy, boggy area that resulted was treacherous amd many people attempting to cross the area were lost.During the middle ages there was only one fixed crossing point beside what became St Sampson’s Marina – “The Bridge”.

The Idea

Sir John Doyle believed that if the French did invade the north, he wouldn’t know whether to fight them as an admiral or a general, because it would depend on the state of the tide – so he decided that the only solution was to reclaim the Braye du Valle.

The States opposed his plans, wanting instead the Braye to be deepened and straightened so that ships could sail up and collect quarried rock from that part of the island.

But being a forceful man, Sir John eventually got his own way.

At that time, during low tide the Braye du Valle consisted of about 350 acres of sand, gravel, clay and bogs, with channels of water one or two feet deep running along its entire length.

There were also areas called salterns, marshy meadows flooded at high tide, and the salt content of the grass made good grazing for cattle.

On the southern shore were saltpans, where sea salt was collected and transported by boat to St Sampson’s.

The only way to cross was via two small bridges by the Vale Church – Pont St Michel and Pont Allaire – three causeways and the main bridge at St Sampson’s – the Pont du Valle.

At high tide, the area of sea was about one mile long by just less than half-a-mile wide. Different accounts put its depth from 10 to 30ft but it was believed that there was enough water for the greatest ships in England to sail.

Before any work could start, however, the British Government had to buy the Braye from the descendants of the original owners.

After settling with these and also the owners of the saltpans for loss of earnings, the total paid for the Braye du Valle was £3,250.

Work Begins

On 1 March 1806, Doyle placed a notice in the Gazette de Guernesey inviting tenders for the construction of dams at either end of the Braye. It stated that work could be done in any manner but that it had to be solid and permanent. It also said that the contractor would be responsible for all repairs for seven years following completion.

Thomas Henry, from Les Mielles in the Clos du Valle, was awarded the contract and he began work on the Grand Havre embankment, at the Vale Church end, on 12 July 1806.

To supplement the civilian labourers, Sir John sent Mr Henry soldiers to help with the work. This cost the latter 10d per day for each man and a shilling for each sergeant.

The embankment at Grand Havre was built from large boulders, a brick wall to keep the sea out and gravel piled up against the wall. At the St Sampson’s end, a stone wall was built parallel to the bridge and this was then reinforced with clay.

Sluices were created at both ends to allow surface water to drain.

After this great feat of strength, with nothing more than the power of man, horse and cart, the land was simply left to drain and to be leached by the weather.

On 27 March 1811, most of the Braye du Valle was bought for £5,000 and part of it was kept by the British Government for training troops.

With the cost of buying the Braye du Valle, £3,250, and the sale price of £5,000, there would seem to be a profit of £1,750. But that doesn’t take into account the cost of the reclamation and there is no mention in the Henry family records how much Thomas was paid for his work.

The six buyers were Pierre Yves Bardel, Henry Giffard, Daniel Mollet, Pierre Mollet, Isaac Carre and Jean Allez and they along with Mr Henry were responsible for the maintenance of the embankments, sluices and douits.

Nowadays, on the surface, there is no obvious sign that Guernsey was once split in two.

Remnants Today

The Vale Pond ... An Echo of the old Braye du Valle

The most obvious is the survival of the name Saltpans. This is where Daniel Hardy and Abraham Le Mesurier made their living capturing sea salt and they were paid £1,750 for the loss of their livelihood caused by the reclamation.A little less obvious is a small parcel of land by the Vale Pond which remains in its natural state, with the pond itself a land-locked ghost of the tidal river it once was.

One hidden reminder is the sea wall that bordered part of the north side of the Braye. Made up of large boulders, it is overgrown with ivy and briar bushes and it is now a listed ancient monument.

St Sampson’s Church is the oldest Church in the island. The church stands near the spot where St Samson of Dol landed from Brittany to convert the islanders to Christianity in 550AD. Before the Braye du Valle was filled in, the church would have stood on it’s shores.

Profile : General Sir John Doyle

Born in Dublin in 1756 after graduating from Trinity College John Doyle joined the army, distinguishing himself in the American War of Independence, before entering the world of Irish politics rising to the post of Secretary of War.

After the start of war with France in 1793 he raised his own regiment, the 87th Regiment of Foot, and served in Holland, Gibraltar and Egypt ahead of his appointment as Private Secretary to the Prince of Wales.

Already commanding the troops in the islands he was made Lieutenant-Governor of Guernsey in 1803, and a Baronet in 1805 and embarked on an ambitious programme of reclamation and rebuilding as part of his defensive strategy against the French.

He was responsible for the draining of the Braye du Valle, which joined the north of Guernsey to the rest of the island for the first time, he constructed roads to enable efficient troop movements and built new fortifications and artillery emplacements around the coast.

During his first year as Lieutenant-Governor Doyle declared a state of emergency in the islands which lasted until Napoleon’s defeat in 1815.

He petitioned the States at length and won over their support as they gave £30,000 to build new forts and batteries.

You must be logged in to post a comment.