1066 and all that … the day the Channel Islands became part of England

1066 – one of the most well known of all historical dates and a pivotal moment in British and Channel Island history. On Sunday the 14th October of that year ‘William the Bastard’, Duke of Normandy (and the Channel Islands), invaded and defeated the Anglo Saxon king of England, so that henceforth the Bastard was to be forever known as William the Conqueror. In this article we look how at how he won at Hastings.

1066 – one of the most well known of all historical dates and a pivotal moment in British and Channel Island history. On Sunday the 14th October of that year ‘William the Bastard’, Duke of Normandy (and the Channel Islands), invaded and defeated the Anglo Saxon king of England, so that henceforth the Bastard was to be forever known as William the Conqueror. In this article we look how at how he won at Hastings.

Claimants to the Throne

Claimants to the Throne

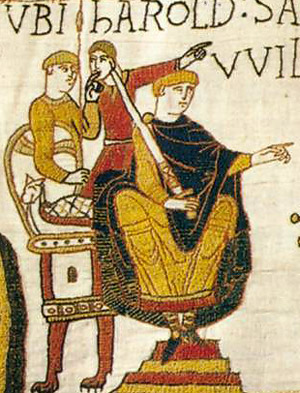

In January 1066, King Edward the Confessor died childless and the throne of England was up for grabs. First came Edward’s brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, who asserted that Edward had named him on his deathbed. But the English barons had no sooner agreed to Harold’s suzerainty than the Norwegian King Harald Hardrada claimed the crown, supported by Harold Godwinson’s exiled brother Tostig. And of course there was a third claimant, a certain Norman duke called Guillaume le Bâtard because of his illegitimate birth. Guillaume, or William, swore that Edward the Confessor had promised the throne to him.

Invasion Number 1

Invasion Number 1

The first invasion of England came in September, launched by Tostig and Harald Hardrada, who landed in Scotland and came down over the border. On hearing of the incursion, King Harold marched his men almost 200 miles in five days and crushed the intruders at Stamford Bridge (near York), killing both his brother and the Norwegian King. But just as his soldiers were recovering from this hard-fought battle, Harold heard that William had landed with another invading force at Pevensey on the Sussex coast. Desperately he turned his army south for another forced march.

Invasion Number 2 and Hastings

Invasion Number 2 and Hastings

On the evening of 13 October Harold caught William by surprise six miles from the coast, near the town of Hastings, but it was already growing late and too dark to fight.

The following morning the two armies faced each other, Harold’s soldiers protected by great war shields and armed with axes, William’s infantry better armoured and equipped with swords and crossbows. But William’s trump was his cavalry, some 2,000 strong.

At first, William’s assaults made little progress against Harold’s wall of shields and William himself was nearly slain, with three of his horses killed under him. After repeated failure to break the enemy line he finally resorted to ruse, ordering his men to pretend to panic and break to the rear. It worked, in spite of Harold’s efforts to restrain his troops, the English line broke in triumph, eager to pursue what they saw as a defeated enemy.

At first, William’s assaults made little progress against Harold’s wall of shields and William himself was nearly slain, with three of his horses killed under him. After repeated failure to break the enemy line he finally resorted to ruse, ordering his men to pretend to panic and break to the rear. It worked, in spite of Harold’s efforts to restrain his troops, the English line broke in triumph, eager to pursue what they saw as a defeated enemy.

With the English streaming towards his retreating men in a chaotic charge, William unleashed his cavalry, which ploughed into the disorganised enemy, cutting them down in hundreds.

Harold still held part of his original line, but many of the English were dead or dying. Resolutely he pulled his men behind their wall of shields, but now Norman arrows constandy bombarded them and they could not return fire as the English archers had all been routed. Before the battle could reach a conclusion, a Norman arrow struck Harold in the eye and killed him (although it must be said that the only ‘evidence’ for this is teh Bayeux Tapstry and even then it’s not clear that it is Harold receiving the arrow).

William the Bastard had vanquished the English and in the years ahead he would subjugate the Welsh and Scots too. Enthroned in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066, he was known henceforward as William the Conqueror.