Christmas Carols – The Oldest ones are the best – Some Origins

They say the old songs are the best and when it comes to Christmas Carols they may well be right.

They say the old songs are the best and when it comes to Christmas Carols they may well be right.

Although Christmas was celebrated in song in the Middle Ages, most carols in use now are less than 200 years old. Only a handful, such as I Saw Three Ships or the decidedly pagan-sounding The Holly and the Ivy, remind us of more ancient yuletides. Carols fell from favour in England after the Reformation because of their frivolity and were rarely sung in churches until the 1880s when the Bishop of Truro (later Archbishop of Canterbury) drew up the format for the Nine Lessons and Carols service, which has remained in use ever since.

So today’s Christmas carols are mostly a Victorian tradition along with many of our other ‘modern’ traditions such as trees, crackers and cards.

Silent Night (1818)

| WORDS : | Josef Mohr |

| MUSIC : | Franz Xaver Gruber |

Arguably the world’s most popular Christmas carol comes in several different translations from the German original. It started out as a poem by the Austrian Catholic priest Father Josef Mohr in 1816. Two years later, Mohr was curate at the parish church of St Nicola in Oberndorf when he asked the organist and local schoolteacher Franz Xaver Gruber to put music to his words.

Arguably the world’s most popular Christmas carol comes in several different translations from the German original. It started out as a poem by the Austrian Catholic priest Father Josef Mohr in 1816. Two years later, Mohr was curate at the parish church of St Nicola in Oberndorf when he asked the organist and local schoolteacher Franz Xaver Gruber to put music to his words.

An unreliable legend has it that the church organ had been damaged by mice, but whatever the reason, Gruber wrote it to be performed by two voices and guitar. It was first performed at midnight mass on Christmas Eve 1818, with Mohr and Gruber themselves taking the solo voice roles.

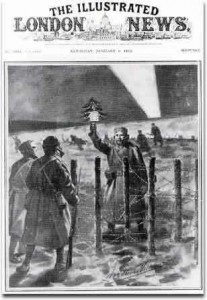

Its fame eventually spread (allegedly it has been translated into over 300 languages and dialects) and it famously played a key role in the unofficial truce in the trenches in 1914 because it was one of the only carols that both British and German soldiers knew.

Good King Wenceslas (1853 or earlier)

| WORDS : | John Mason Neale |

| MUSIC : | Traditional, Scandinavian |

The Reverend Doctor Neale was a high Anglican whose career was blighted by suspicion that he was a crypto-Catholic, so as warden of Sackville College – an almshouse in East Grinstead – he had plenty of time for study and composition. Most authorities deride his words as “horrible”, “doggerel” or “meaningless”, but it has withstood the test of time. The tune came from a Scandinavian song that Neale found in a rare medieval book that had been sent to him by a friend who was British ambassador in Stockholm.

The Reverend Doctor Neale was a high Anglican whose career was blighted by suspicion that he was a crypto-Catholic, so as warden of Sackville College – an almshouse in East Grinstead – he had plenty of time for study and composition. Most authorities deride his words as “horrible”, “doggerel” or “meaningless”, but it has withstood the test of time. The tune came from a Scandinavian song that Neale found in a rare medieval book that had been sent to him by a friend who was British ambassador in Stockholm.

There really was a Wenceslas – Vaclav in Czech – although he was Duke of Bohemia, rather than a king (check out our article Good King Wenceslas – The Story behind the Carol). Wenceslas (907–935) was a pious Christian who was murdered by his pagan brother Boleslav; after his death a huge number of myths and stories gathered around him. Neale borrowed one legend to deliver a classically Victorian message about the importance of being both merry and charitable at Christmas. Neale also wrote two other Christmas favourites: O Come, O Come Emmanuel (1851) and Good Christian Men, Rejoice (1853).

Once in Royal David’s City (1849)

| WORDS : | Cecil Frances Humphreys Alexander |

| MUSIC : | HJ Gauntlett |

Cecil Frances Humphreys was born in Dublin to a comfortable Anglican family. In 1848 she published Hymns for Little Children, a book of verse explaining the creed in simple and cheerful terms and which gave us three famous hymns. So to the question who made the world, the answer was All Things Bright and Beautiful. Children’s questions on the matter of death were answered with There is a Green Hill Far Away, while Once in Royal David’s City told them about where Jesus was born. The book was an instant hit and remained hugely popular throughout the 19th century.

Cecil Frances Humphreys was born in Dublin to a comfortable Anglican family. In 1848 she published Hymns for Little Children, a book of verse explaining the creed in simple and cheerful terms and which gave us three famous hymns. So to the question who made the world, the answer was All Things Bright and Beautiful. Children’s questions on the matter of death were answered with There is a Green Hill Far Away, while Once in Royal David’s City told them about where Jesus was born. The book was an instant hit and remained hugely popular throughout the 19th century.

The organist and composer Henry Gauntlett put music to it a year later and nowadays it traditionally opens the King’s College Cambridge Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols.

Cecil threw herself into working for the sick and poor, turning down many requests to write more verse. Much of the proceeds from Hymns for Little Children went to building the Derry and Raphoe Diocesan Institution for the Deaf and Dumb.

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing (1739 or earlier)

| WORDS : | Charles Wesley |

| MUSIC : | Felix Mendelssohn |

Charles, the brother of Methodist founder John Wesley, penned as many as 9,000 hymns and poems, of which this is one of his best-known. It was said to be inspired by the sounds of the bells as he walked to church one Christmas morning and has been through several changes. It was originally entitled Hark How All the Welkin Rings – welkin being an old word meaning sky or heaven.

Charles, the brother of Methodist founder John Wesley, penned as many as 9,000 hymns and poems, of which this is one of his best-known. It was said to be inspired by the sounds of the bells as he walked to church one Christmas morning and has been through several changes. It was originally entitled Hark How All the Welkin Rings – welkin being an old word meaning sky or heaven.

As with most of his hymns, Wesley did not stipulate which tune it should be sung to, except to say that it should be “solemn”. The modern version came about when organist William Hayman Cummings adopted it to a tune by German composer Felix Mendelssohn in the 1850s. Mendelssohn had stipulated that the music, which he had written to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the invention of the printing press and which he described as “soldier-like and buxom”, should never be used for religious purposes.

God rest you merry, Gentlemen

| WORDS : | Unknown |

| MUSIC : | Unknown |

This is thought to have originated in London in the 16th or 17th centuries before running to several different versions with different tunes all over England. The most familiar melody dates back to at least the 1650s when it appeared in a book of dancing tunes. It was certainly one of the Victorians’ favourites.

If you want to impress people with your knowledge (or pedantry), then point out to them that the comma is placed after the “merry” in the first line because the song is enjoining the gentlemen (possibly meaning the shepherds abiding in the fields) to be merry because of Christ’s birthday. It’s not telling “merry gentlemen” to rest!