Modern Compensation Culture and the Ancient Practice of Wergeld

If there is one thing that is a blight on modern life it is the rise of ‘compensation culture’. The idea that someone else is always to blame and you are entitled to some compensation no matter what.

If there is one thing that is a blight on modern life it is the rise of ‘compensation culture’. The idea that someone else is always to blame and you are entitled to some compensation no matter what.

Our propensity to seek financial redress for any injury, insult or inconvenience is often portrayed by the press as one of the worst traits of the 21st century and is often reinforced by frequent headlines of undisclosed settlements measured in six or seven figures and mammoth payouts awarded by the courts.

Indeed, much of the time the courts do not even get a look in as financtal reward can be reaped by the mere raising of a complaint or threatening of a claim.

American Origins ?

In Britain we like to bemoan that this is a modern disease imported from our ‘cousins across the Atlantic’ for whom damages appear to be an antidote to almost everything. It is they we look to blame for infiltrating our values of being ‘good-sports’ with such an unsavoury attitude. Whereas in those halcyon days of yore we acted with virtue and self-restraint if we were wronged by our neighbours.

However this a rather rose-tinted view, and nostalgic vision of a Britain which never was. Because those with a keen Interest in Anglo Saxon England will be quick to see the hypocrisy of such a notion. Why? Because In reality the foundation of this compensation culture lies much closer to home.

Feud Culture

It is to the Dark Ages that we need to turn to where we find a society regulated by a strict, honour-based, feud culture.

This feud culture existed in an age prior to the emergence of a formal interventionist and regulatory state. To ensure that ‘wrongs’ did not go ‘un-righted’ it was your familial duty to avenge the slaying of kindred through a blood feud – the vengeful killing of the perpetrator.

However, this would for obvious reasons result in a cycle of spilt blood which would only serve to weaken both sides of the feud.

Wergeld

So an emminently practical solution evolved where it became acceptable, and equally honourable, for the guilty party to instead to pay financial compensation to the innocent party in lieu of blood, known in Anglo Saxon England as Wergeld.

So an emminently practical solution evolved where it became acceptable, and equally honourable, for the guilty party to instead to pay financial compensation to the innocent party in lieu of blood, known in Anglo Saxon England as Wergeld.

Rather than viewing this payment as a penalty for the crime we need to see the Wergeld as a means to end the need for further bloodshed. That said, it also came to be extended to possessions, so that any item of property which was stolen or damaged held a compensatory value too.

Whilst Wergeld was undoubtedly a more civilised alternative to feuding, it was by no means egalitarian. Quite the opposite in fact because it enshrined inequality by reinforcing the hierarchical nature of society through a three-tier system of life values worth 1200, 600 and 200 shillings respectively. Thus the killing of a peasant was worth 6 times less than the killing of an Ealdorman.

Feud culture and Wergeld ceased to exist as kings sought to centralise their own power under a formal system of law and order and the arrival of Christianity in Britain in 597 AD provided the excuse necessary to discredit the feud system, arguing that homicide was a crime not only against God but by extension the King himself.

Textus Roffensis

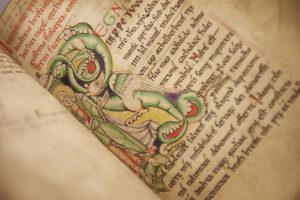

In 1122, nearly a century before, Magna Carta (1215), a monk in Rochester Cathedral Priory carefully copied out the laws issued by Ethelbert, the first Christian King of Kent (AD 560-515). Ethelbert’s law code was the first codified statement of English law written in English and is the earliest known copy of Ethelbert’s Anglo-Saxon law code. It survives within Textus Roffensis – the ‘Book of Rochester’.

In 1122, nearly a century before, Magna Carta (1215), a monk in Rochester Cathedral Priory carefully copied out the laws issued by Ethelbert, the first Christian King of Kent (AD 560-515). Ethelbert’s law code was the first codified statement of English law written in English and is the earliest known copy of Ethelbert’s Anglo-Saxon law code. It survives within Textus Roffensis – the ‘Book of Rochester’.

It’s a fascinating document that aptly shows the transition from Feud culture and Wergeld to the codifying of power under a written system of law, containing as it does a list of suitable compensations …

if an ear was struck off, 12 shillings in compensation was to be paid; if an eye was put out, compensation was 50 shillings; for the loss of the four front teeth, 6 shillings for each; if someone struck another on the nose with a fist, 3 shillings compensation was due; if a person broke into a commoner’s home he was to compensate with 5 shillings; accomplices who entered after the person who broke in must pay 3 shillings and thereafter one shilling according to the order in which they broke in.

You can now see the whole book in amazing detail online here >>>

So we shouldn’t be too quick to point our fingers and blame a subversive ethos from afar when in fact the roots of the compensation culture lie historically on our side of the Atlantic.

Perhaps we can also be grateful at least that our judicial systems, unlike those in the ‘land of opportunity’, do not ordinarily award on top of compensation vast punitive damages designed to punish and deter defendants.