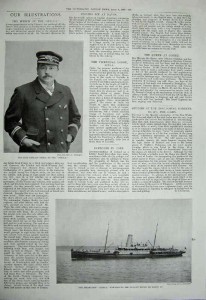

The S.S. Stella

The Steam Ship “Stella” has entered local history as a byword for tragedy when she was sadly wrecked in 1899 off of Alderney. The disaster has been described as the ‘Titanic of the Channel Islands’. The loss of the Stella caught the public imagination. Heroic deeds, real or imagined, were commemorated by memorials, and in poetry and prose by the poet laureate.

The Channel Islands Crossing

During the nineteenth century increased wealth and improvements in technology led to a growth in travel. The Channel Islands began to be a popular destination for travellers from mainland Britain. A summer season paddle-steamer service from Southampton to the Islands operated as early as 1824. In 1840 Southampton was linked by railway to London, and the London and South Western Railway Company saw the operation of ferryboats from the port as a natural extension of its service. Its success was quickly imitated by other companies, notably the Great Western Railway working via Weymouth.

The Quest for Speed

By 1860 the Channel Islands were served by ferries operated by two railway companies – the London and South Western Railway from Southampton; and the Great Western Railway from Weymouth. Rivalry between the companies and the towns was intense, with first one partnership, then the other, holding the advantage. Speed became the vital issue, supported by improvements in steamship technology. Accidents, even a disaster, became inevitable.

In 1877 the London & South Western Railway introduced a daily service to the Channel Islands with fast screw steamers. With a dredged harbour, an extended pier, and three new GWR twin-screw steamers to provide a daily service, Weymouth was ready to strike back in 1889. The GWR advertisements proclaimed Weymouth as the “Quickest and Best” route and passenger numbers rose rapidly. Within a year Weymouth was again the prime port for the Islands. Not to be outdone, the L & SWR also ordered three new twin-screw steamers (Frederica, Lydia and Stella) and began intensive advertising which relied heavily on publicising their best crossing times.

Boats were by now timed to arrive together at Guernsey, and from the Casquets down would sometimes race in parallel, urged on by passengers. The race was then on to St. Helier where only one ship could enter at a time, and where a low-tide could prevent access to the harbour, forcing a runner-up to land passengers and luggage by dinghy, which lost the Company money and prestige.

Racing did not occur on every crossing and officially never took place. The companies’ stated intention was only to cut their best times, and publicity never mentioned the opposition. Nevertheless, the competition caught the public imagination, particularly in the Channel Islands, and was eagerly reported by the newspapers.

The Stella

The Stella entered service in November 1890. Her two powerful compound steam engines drove twin screws to give her a top speed of over 19 knots. She was licensed to carry 750 passengers, with sleeping accommodation for 240. No expense was spared on passenger comfort and she was fitted with electric lighting. She was a product of “state of the art” technology and superb craftsmanship.

The Casquets

The main Casquets reef lies seven miles west of Alderney and extends nearly a mile east-west, with further large banks to the north-east and south. Apart from the numerous rocks permanently above water, some of which are eighty feet high, there are extensive shoals and submerged ledges, some with only three feet of water over them at high tide. Within the reef there is a constant clashing of tides with fierce overfalls that can run at ten knots over the uneven bottom. At low water the tide rips through the gullies between the rocks like a mill race. Nearly three hundred ships are recorded as having come to grief on the Casquets.

The Fateful Voyage

On Maundy Thursday, April 30th 1899 the Stella was on the first daylight service of the season from Southampton to the Channel Islands. She encountered fog on the way but continued to steam at full speed. When the Stella had run the estimated distance to the Casquets, nothing could be seen of the lighthouse. At 4.00pm Simultaneously :. A foghorn of immense strength sounds directly above Stella; The bow lookout yells “Stop her!”; An immense rock looms out of the fog 80 yards ahead. Reeks orders “Full Speed Astern” and spins the wheel hard to starboard. The Stella scrapes her port side. Another rock looms dead ahead, and the ship runs over submerged rocks at full speed. Her engines are torn from their mountings and water pours in along half her length. She runs into clear water and begins to settle, stern first. The Stella sank in 8 minutes. Of her passengers and crew 105 were lost and 112 saved.

The Stella was 2.5 to 3 miles ahead of where Reeks believed her to be. With the tidal conditions prevailing she should have been 1.5 miles clear of Casquets to the west. Why she wasn’t remains a mystery.

“Ladies and Children First!”

Captain Reeks immediately ordered “Boat Stations. Ladies and children first!” The boats were out with remarkable speed and calmness. In an air of curious calm Captain Reeks’ orders were speedily obeyed – the crew went to their boat stations and the stewards to assist passengers and distribute lifejackets. Problems arose in launching the port lifeboat due to the angle of the ship. A number of passengers including women waited to board it but it capsized as it was finally lowered. Passengers and crew leapt into the sea as Stella rose until she was almost vertical, remained poised for a moment, then slid abruptly down. Eight minutes had elapsed since Stella’s initial striking.

“The News hits”

Fears for the Stella began to grow by nightfall. Telegrams passed between the fog shrouded Channel Islands and Southampton and anxious relatives began to gather. Nothing was known until the morning of Good Friday when the night ferries Vera and Lynx entered St. Peter Port and landed the first survivors. Searches of the Casquets area were carried out and slowly the scale of the disaster became evident. By Saturday the Islands were in mourning and in England the newspapers published the tragic news.

The Survivors

The ship’s lifeboats were lowered very speedily. Had they not been, the loss of life would have been much greater. Most of the women and children were saved. The four fully loaded boats drifted for many hours at the mercy of rocks and fierce tides. The first two boats were not found by the Vera until 7am on Good Friday. One boat drifted for 23 hours before being rescued off Cherbourg.

The first bodies were recovered on Good Friday. The dead continued to be found for weeks after. One body was located at the mouth of the River Seine, and the final corpse was washed up on Guernsey nine months later. Most were found floating in their lifebelts, having died from exposure rather than drowning.

The Enquiry

The Board of Trade Enquiry opened amid great public interest on Thursday April 27th 1899 at the Guildhall, Westminster, and continued for six days. The reputation of the L & SWR was at stake and heavy financial loss was a possibility if the Company was found to be negligent. The sole surviving officer of the Stella, Second Officer George Reynolds, bore the brunt of the questioning. The ship’s operating procedures were brought into question and particularly the speed of the Stella at the time of the disaster. Racing was suggested.

The final verdict was :

The Stella’s speed was rashly excessive for the conditions. At 3.55 the ship should have been on dead slow or stopped and the lead used to check her position. Because neither of these was done, the assessors were forced to conclude that the Stella was not navigated with proper and seamanlike care.

Aftermath

The Stella represented “state of the art” late nineteenth century technology, but her navigation depended on methods which were medieval. Less than two months after reporting the Stella disaster, the newspapers carried coverage of a revolutionary new system of “wireless” telegraphy developed by Signor Marconi. Trinity House was already investigating the possibility of putting wireless transmitters on all dangerous reefs to emit danger signals to ships.

You must be logged in to post a comment.