Sinterklaas – A very Dutch tradition

The figure of Sinterklaas and the traditions that surround him are quintessentially Dutch. Nowhere else in the world is the figure of Saint Nicholas celebrated in a similar way. Here’s how the Dutch celebrate St Nicholas …

The first thing to realise is that he has nothing to do with Christmas. Christmas celebrations and Sinterklaas are quite unrelated. Christmas decorations and preparations are not even begun until after celebrating Sinterklaas on December the 5th.

St. Nicholas’ Feast Day, December 6th, is observed in most Roman Catholic countries primarily as a feast for small children. But it is only in the Low Countries – especially in the Netherlands – that the eve of his feast day (December 5th) is celebrated nationwide by young and old, Christian and non-Christian, and without any religious overtones.

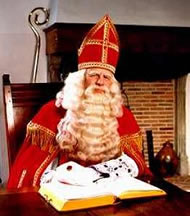

Athough Sinterklaas is always portrayed in the vestments of the bishop he once was, his status as a canonized saint has had little to do with the way the Dutch think of him. Rather, he is a kind of benevolent old man, whose feast day is observed by exchanging gifts and making good-natured fun of each other. It so happens that the legend of St. Nicholas is based on historical fact. He did actually exist. He lived from 271 A.D. to December 6th, 342 or 343. His 4th century tomb in the town of Myra, near the city of Anatolia in present-day Turkey, has even been dug up by archaeologists.

All Dutch children know that Sinterklaas (the name is a corruption of Sint Nikolaas) lives in Spain. Exactly why he does remains a mystery, but that is what all the old songs and nursery rhymes say. Whatever the case may be, in Spain he spends most of the year recording the behaviour of all children in a big red book, while his helper Black Peter stocks up on presents for next December 5th. In the first weeks of November, Sinterklaas gets on his white horse, Peter (“Zwarte Piet”) swings a huge sack full of gifts over his shoulder, and the three of them board a steamship headed for the Netherlands. Around mid-November they arrive in a harbour town – a different one every year – where they are formally greeted by the Mayor and a delegation of citizens. Their parade through town is watched live on television by the whole country and marks the beginning of the “Sinterklaas season”.

The old bishop and his helpmate are suddenly everywhere at once. At night they ride across Holland’s’ rooftops and Sinterklaas listens through the chimneys to check on the children’s behaviour. Piet jumps down the chimney flues and makes sure that the carrot or hay the children have left for the horse in their shoes by the fireplace is exchanged for a small gift or some candy. During the day, Sinterklaas and Piet are even busier, visiting schools, hospitals, department stores, restaurants, offices and many private homes. Piet rings doorbells, scatters sweets through the slightly opened doors and leaves basketfuls of presents by the front door.

The Dutch are busy too – shopping for, and more importantly, making presents. Tradition demands that all packages be camouflaged in some imaginative way, and that every gift be accompanied by a fitting poem. This is the essence of Sinterklaas: lots of fun on a day when people are not only allowed, but expected, to make fun of each other in a friendly way. Children, parents, teachers, employers and employees, friends and co-workers tease each other and make fun of each others’ habits and mannerisms. Another part of the fun is how presents are hidden or disguised. Recipients often have to go on a treasure hunt all over the house, aided by hints, to look for them. They must be prepared to dig their gifts out of the potato bin, to find them in a jelly pudding, in a glove filled with wet sand, in some crazy dummy or doll. Working hard for your presents and working even harder to think up other peoples’ presents and get them ready is what the fun is all about.

The original poem accompanying each present is another old custom and a particularly challenging one. Here the author has a field day with his subject (the recipient of the gift). Foibles, love interests, embarrassing incidents, funny habits and well-kept secrets are all fair game. The recipient, who is the butt of the joke, has to open his/her package in public and read the poem aloud amid general hilarity. The real giver is supposed to remain anonymous because all presents technically come from Sinterklaas, and recipients say out loud “Thank you, Sinterklaas!”, even if they no longer believe in him.

Towards December 5th, St. Nicholas poems pop up everywhere in the Netherlands: in the press, in school, at work and in both Houses of Parliament.

On the day of the 5th, most places of business close a bit earlier than normal. The Dutch head home to a table laden with the same traditional sweets and baked goods eaten for St. Nicholas as shown in the 17th-century paintings of the Old Masters. Large chocolate letters – the first initial of each person present – serve as place settings. They share the table along with large gingerbread men and women known as “lovers”. A basket filled with mysterious packages stands close by and scissors are at hand. Early in the evening sweets are eaten while those gathered take turns unwrapping their gifts and reading their poems out loud so that everyone can enjoy the impact of the surprise. The emphasis is on originality and personal effort rather than the commercial value of the gift, which is one reason why Sinterklaas is such a delightful event for young and old alike.

You must be logged in to post a comment.