Roman Guernsey – Lisia

In the first century BC the Iron Age tribes in Gaul came under attack from the Roman legions under Julius Caeser. By 52BC and after eight years of violent warfare, all of Gaul was conquered when he finally defeated that last of the Gaulish tribes resisting the legions at Alesia. With the surrender of the Gaulish Chieftan Vercingetorix all of Gaul had passed into the Roman sphere and it is likely that Guernsey also became part of the Roman Empire around the same time.

In the first century BC the Iron Age tribes in Gaul came under attack from the Roman legions under Julius Caeser. By 52BC and after eight years of violent warfare, all of Gaul was conquered when he finally defeated that last of the Gaulish tribes resisting the legions at Alesia. With the surrender of the Gaulish Chieftan Vercingetorix all of Gaul had passed into the Roman sphere and it is likely that Guernsey also became part of the Roman Empire around the same time.

Moving into the Roman World

Contrary to to popular belief the Romans didn’t call Guernsey Sarnia. It is likely that the name they gave it was Lisia. Recent research would seem to indicate that the term Sarnia might have been the Latin name for Sark; although Sarnia remains the island’s traditional designation.

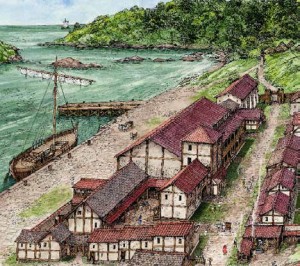

Life in the islands would have continued much as it did before Lisia became part of the Empire. A small town grew up in St Peter Port, although it is not known what it was called. Archaeologists have found stone Roman buildings at La Plaiderie and underneath the Town Markets. It is thought that they were warehouses used as part of a trading post. Finds on the site include creamation urns along with a votive offering of a complete pig. Pigs were an intergral part of Roman religious rites. This coupled with the burial urns suggest that the inhabitants of Guernsey had pretty much adopted Roman religion & cultural practices. Out in the countryside, there may have been a large house, villa or even a fort near the Castel Church, which has Roman tile built into its walls. Roman buildings also lie beneath the sand at Longy Common in Alderney.

Trade

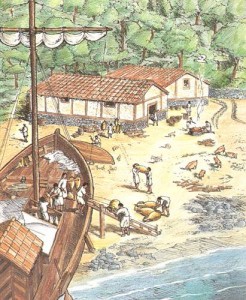

Roman merchant ships sailed north from the Mediterranean, from western Gaul and Iberia (Spain) bringing cargoes to northern Gaul, Britain and Germany. Ancient sailors preferred to sail within sight of land, so Lisia was a good place to aim for and provided a sheltered harbour with fresh water. The salt that was manufactured, just outside St Peter Port at La Salerie, would also have been valuable for preserving food on long voyages. Guernsey granite was also actively being exported and has been found at a Roman Villa in Fishbourne West Sussex.

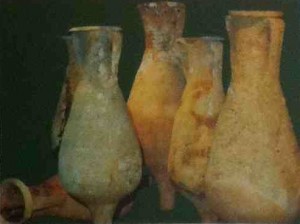

No doubt some of the cargo would be sold or exchanged in the town, including Roman style pottery and fine goods. Large storage jars known as amphorae have been found that once would have contained wine, olive oil, fish sauce amongst other expensive foods.

“Asterix”

Roman Amphorae found on a Roman wreck off St Peter Port

Around 280 AD a Roman ship caught fire in the harbour and sank. We know this as the wreck was found and raised by divers between 1984 and 1986 and its timbers preserved. Pottery on board from as far away as Spain and Algeria was found and illustrates Guernsey’s strategic importance on the trade route from the southern Mediterranean. The ship raised in 1986 was The St Peter Port wreck, dubbed by the media “Asterix”, after the famous French cartoon character of that same name. At least one further Roman ship is known to have sunk in the Little Russel, a short distance out from the harbour.

There is no evidence (yet) that Roman soldiers were ever stationed in Guernsey.

Decline and Fall

During the 3rd and 4th centuries AD Britain and Gaul came under attack by pirates and ‘barbarian’ raiders including the Saxons and the Franks. It became increasingly difficult for the Roman Empire to keep control. In AD 410, Rome was even sacked by the Visigoths. The Emperor decided to abandon Britain and the Legions were withdrawn.

Further civil unrest followed as Empire began to decline. Gaul became a battleground between official Roman armies, rebel Roman generals and barbarian tribes. Roman influence would have declined in the islands but no official end to ‘Romano-Guernsey’ can be defined as the ‘dark ages’ or early medieval period began.

LEARN MORE : The Guernsey Gallo-Roman Wreck (Asterix) ...

Discovery

Except for one day each year, when access is traditionally allowed (Christmas Day), diving in St Peter Port harbour is normally impractical due to the volume of traffic. Local diver Richard Keen was exercising this right to dive for scallops in the harbour, on Christmas Day in 1982, when he noticed the timbers of a wreck protruding from the sediment. The timbers were located in the centre of the narrow entrance to the modern harbour and were clearly being exposed (and therefore under threat) by the propeller wash of vessels passing overhead. The wrecked vessel seemed very heavily built, flat bottomed and about 20 metres long, though at this stage there was nothing to suggest its great antiquity.

The following year, a return visit to the site lead to the discovery of associated Roman tile fragments and the age of the wreck began to be suspected. A timber fragment was subsequently dated to AD 110 ± 80, thus alerting everyone to the importance of the site and also to the combined danger it faced – from imminent destruction by harbour traffic and biological attack of the newly exposed timbers. A further, more potent threat was the planned intention of the local authorities to dredge the harbour, to allow the passage of larger ferries. Urgent action to was required, to save the wreck from total destruction.

Excavation

Excavation took place in two main campaigns, in November 1984 and March 1985. A short third campaign took place in September 1986 with additional dives being made around the site by Richard Keen (occasionally with other divers) until 1988. Essentially this was a rescue excavation, carried out in very difficult conditions by a mixture of archaeological and local divers, under the direction of Dr Margaret Rule. Harbour traffic frequently disrupted operations, lowered visibility generally and also damaged partially excavated material. During the winter of 1984/85 the site was buried under tons of sandbags but even these were disturbed several times and had to be laboriously replaced by local divers. Despite the difficulties, the wreck site was properly surveyed, the material within the wreck was excavated and the released timbers were then removed to a holding tank, to await conservation.

Type of Vessel

The ship was a cargo vessel, constructed entirely of oak. It had a flat bottom and, although the bow section was missing, is thought to have had a symmetrical shape, with stem and stern posts butted on to the ends of the three-part keel. The planks (or strakes) making up the bottom and sides of the ship were nailed onto an estimated 40 substantial timber frames, using iron nails. Smaller planks (or stealers) were inserted between the larger strakes, to assist in forming the curvature of the hull. All the planks were simply butted together (carvel built) and the joints were caulked with wood shavings. The iron nails themselves were bedded into caulking rings of moss, and the ends of the nails were bent over (clenched) on the inside of the frames, to make the structure secure. The ship was essentially built following celtic traditions, known from other wreck-sites but incorporated technological advances, such as a bilge-pump with bronze bearings, from the Mediterranean tradition.

The ship was originally some 25 metres in length, with a maximum beam of some 6 metres and a height to the gunwale of at least 3 metres, possibly more. It was propelled by sail, carried on a single mast of at least 13 metres in height and located approximately one third of the ships length from the bow. The mast was stepped into one of the massive floor timbers and may have been supported at deck level by a mast partner. Square sails seem to have been the norm for the region but it has been suggested that a fore-and-aft lugsail might have been more appropriate.

Finds from the site suggest that the ship may have had a small structure with a tiled roof in the aft area, which probably contained the cooking and food preparation area. The quantity of pottery and other ‘personal’ items found suggests a crew compliment of three.

Circumstances of Loss

The Guernsey ship was lost due to a fire on board, which effectively destroyed everything above the waterline. It was lost in relatively shallow water, quite close to the shore, so a number of pertinent observations may be quoted from the monograph describing the wreck, particularly with respect to the relative absence of cargo evidence:

‘The wreck may have been only two to three metres below low water mark in the third century and therefore accessible to even the most primitive salvage techniques.’

‘A totally flammable, biodegradable or buoyant cargo carried separate from the preserving pitch would leave no trace. Something very combustible burned the face of the timbers in the inter-frame spaces.’

‘The ship was probably at anchor or grounded when the fire broke out. This opens up the possibility that the cargo had already been unloaded.’

‘If a military transport role is postulated, then any troops or horses carried would probably be ashore whilst the ship was in harbour.’

‘It is unlikely that the ship was out of commission, due to the numbers of personal possessions and food remains found.’

(Rule and Monaghan, 1993)

RELATED ARTICLES

| Asterix – Guernsey’s Own Roman Wreck | |

| Guernsey Celts & Guernsey Romans – A Timeline | |

| Roman Jersey | |

| When Worlds Collide : The Romans and Jersey’s Celtic Treasure Hoards |

You must be logged in to post a comment.